I wrote this article some years ago and tried to get it published while I was still a civil servant. You won't be surprised to hear that I was refused!!

I apologise that it is very long. I am still searching for the button that allows me to split long articles so that only introductory paragraphs appear on the front page from which you determine your interest.

The first section covers the so-far un-told story of the first 24hrs inside Kosovo in June 1999.

I assure you its a good read - if you have time!! Go on, you might enjoy it.

If anyone wants to publish it more widely, just let me know.

Introducing the Forces Communications Group

The marriage of civilian and military media advisers inside the MOD press office has never been easy but as changes to the structure and operation are finally made, Richard Bailey, a former Senior Government Press Officer in Whitehall and former Army Press Officer, puts a new perspective on the problem.

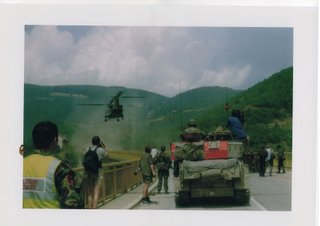

12 June 1999 came to a brief stop for me on the tarmac of Pristina airport surrounded by Russian soldiers, Serbian soldiers, a Company of 1 Para and about 25 highly eminent British journalists (including Kate Adie, Tim Butcher, Michael Evans, Ross Benson, Keith Graves...). We all stood, soaked by a late afternoon downpour, waiting for General Sir Mike Jackson to arrive and proclaim the entry into Kosovo as the complete success that it was. The NATO force had pressed 50 miles into Kosovo in a single day without a shot being fired or a voice raised. The vacuum left by a retreating Serbian Army had been filled before it appeared and even the unexpected appearance of a Russian battalion was to be hailed as a triumph of allied co-operation. General Jackson appeared in his helicopter, stepped out, addressed the waiting media and slipped away to welcome the Russians in private. Priceless PR for a fabulous organisation. But what came next was the most nerve wracking and defining twelve hours of my life.

It was now about half past six in the evening, dusk was falling and as we turned to leave the airport, the plan fell to pieces. The Paras had vanished into thin air, and at that precise moment 4 Army press officers, and 25 journalists, including some instantly recognisable names, were the furthest forward element of the NATO force. But we had no maps, no radios, two vehicles (both media armoured cars), insufficient rations, 4 pistols with a total of 150 rounds of ammunition and no idea where anyone was. We walked quickly but confidently back the way we had come. As we walked through a Russian checkpoint, however, and darkness fell, that confidence fell away and the only Serbian speaker in the group, a journalist, made the crucial decision.

Suddenly veering off the road he marched straight up to the nearest house, rapped on the door and within minutes the occupants were happily walking off into the darkness and we were moving in. Unable to raise anyone on our mobile phones, we settled down for the night, cooked what little food we possessed and chatted nervously about what we would do if either the Serbs or the Russians decided they didn’t want to play General Jackson’s game after all. Two press officers would be on guard during the night - for all the good it would do us. It was as much habit as purpose.

In the morning we rose, washed and shaved (again habit really) and as we gathered together ready to walk further down the road, salvation arrived in the form of a large Army truck. Minutes later we pulled up outside a barrack building where we found our lost Paras sharing a billet with a Company of Serbs. Minutes after that we were back with our Headquarters. No relieved welcome, just the classic British understatement – “Where the bloody hell have you been??!”

I tell that story because it helps to describe the true chaos of military operations and ultimately the sort of challenge that military media relations faces. I have every confidence that during those few hours of uncertainty, our esteemed media colleagues probably thought we were the most useless bunch of press officers in the Army. But of course what I haven’t told you is that none of us were press officers at all – we were just ordinary infantry officers, with little or no training, looking after the media because it had to be done. But these journalists commanded an audience in the UK alone of approaching 20 million people, and would help these people form a life long opinion – Army good or Army bad. I vowed then never to be useless in the eyes of the media again.

Forces media relations is a complex issue tangled in politics and history. In a nutshell, the MOD is the Government Department where the culture gap between the politicians and the civil servants (soldiers, sailors and airmen) is at its widest. Politics thrives in the glare of the media and the public eye. The Forces prefer the shadows and most certainly do not seek any media intrusion. Changes have recently been made to the structure and running of the MOD press office after the most intensive period of British military activity since WW2. The PR changes were driven by politics and now, despite being such great leaders in so many different fields, the military finds itself being led. So the question I wish to address in this essay is solely that concerning the attitude of the modern military towards the media and its public image.

So why then have the politicians been so determined to re-organise the press office? Is this an example of an overbearing Government media machine shifting the goal posts? Well, no, I don’t think so. In actual fact, I believe that such radical steps have been made necessary by decades of military malaise and frankly they were necessary to bring some certainty to the operation. For too long the Forces have ignored public relations and treated it with a mixture of disdain and derision.

I need look no further that my own entry into military media relations for the finest example of that malaise. In 1995, whilst serving with my Regiment in Londonderry, I was summoned to the Commanding Officer’s office to be told that we had to have a press officer while we were in Northern Ireland. Nobody seemed to know what that job actually was, how to do it or how we might measure success. He had to have a name beside the appointment and that name was mine.

It is pure chance that I discovered, to my pleasure, that I was better at PR than I ever had been at soldiering and I had stumbled on a second career just as my first was reaching a ceiling. But across the Army alone there are about 100 officers who are summoned in just the same way and who despise every moment of it, their only thought of a career in tatters. Worse still, neither those doing the appointing nor those being appointed seem able to recognise just how much damage they could do to the reputation of their own beloved employer.

It is only now, of course, that I fully understand PR as a profession in the same way that accountancy or dentistry is a profession. It is a crucial profession that can positively and negatively influence morale, recruiting, budgets, and most importantly public opinion and support. The Army is no less a corporate body with a desperate need to manage its image and reputation than Marks and Spencer or British Gas, but it doesn’t seem to see things that way. The forces have always been troubled by public relations but good communications would help to bring consistency to that age old problem - the forces image and reputation:

“O it's Tommy this, an' Tommy that, an' "Tommy, go away”,

But it's "Thank you, Mister Atkins", when the band begins to play,

The band begins to play, my boys, the band begins to play,

O it's "Thank you, Mister Atkins", when the band begins to play.”

Tommy by Rudyard Kipling

[It hasn’t always been that way. The most famous General of all – Montgomery – understood spin better than anyone. When he arrived in North Africa to tackle Rommel, Montgomery was no better a tactician or strategist than Auchinleck. Montgomery won because he instinctively knew how to make the 8th Army a corporate brand whose soldiers felt proud to serve. Communication, image, reputation were his key weapons in convincing his men that they could fight together and win, and he created an Army that was so well PR’ed that it remains one of the most recognisable military brands in the world – The Desert Rats.]

The Army has seen sense in relation to so many professions over the years. The establishment of the Royal Army Medical Corp in 1860 underlined the understanding that doctors best serve their soldiers when they are an integrated and respected part of the service. Unless you understand military life and are a part of it, you cannot hope to get the balance of humanity and ruthlessness right. Few soldiers can pull the wool over an Army doctor and most Army doctors can maintain a fit and healthy battalion. The same principle applies to engineering, mechanics, dentists, vets, cooks and musicians. No Commanding Officer would ever summon an Officer and expect him to fix the Land Rovers or the guard dogs. In every case there is an established Army Corp appropriately distributed around the Service, so that the right jobs are done by the right professionals. Commanding Officers may be able to tell the mechanics which vehicles to fix but they do not tell them how to fix them. The very best example is the Army Legal Service (ALS). Here is a group of 100 or so Army lawyers spread around the various Headquarters employed to ensure that military law is applied properly and fairly but with a full understanding of the military context. One and all are professionals first, soldiers second but able to perform under the highest pressure and in the most difficult of circumstances with the full respect of their infantry or artillery colleagues because they walk the walk and live the life.

I imagine you have worked out where this is leading. So, yes, if all of these are respected professions which have been formally integrated into the Forces, why not Communications? How can the Forces be persuaded to respect and understand public relations? How can this gulf of distrust between civilian and military be bridged? Why is there no uniformed, trained and respected professional in each Regiment capable of ensuring that the reputation of that unit is properly maintained? I spent the hours of 12 June 1999 prior to arriving at Pristina airport at the head of a 2000 vehicle convoy dealing with the only element of the plan which no-one had mentioned or considered – the saturation of this tiny road into Kosovo with media. Every time we stopped at a Serb check point, I alone had to keep at least 10 cameras and twice as many journalists away from the Brigadier as he negotiated free passage. I alone had to marshal the eyes of the world safely and professionally without training or direction. (Best day of my life!)

I believe that the MOD must immediately create a new tri-service unit for professional communicators. They must be professionals first and soldiers, sailors and airmen second. The Unit must have the simultaneous respect of the Services, the media and the communications profession. It is a tall order but eminently achievable. Its planning and media management on operations would be an attribute to commanders and it would represent and stand up for the needs and demands of good communications in everything the Forces do. It would recruit young people with a lust for life and adventure and with a little proven experience in the communication industry. Volunteers would be trained in military skills and professional skills before being fully integrated into the Forces. Just like the Doctors, Dentists, lawyers, vets and chaplains, they would then work, live and play with the forces they serve but with one foot firmly anchored in the real world they communicate with. It can be done and would prove an exciting, challenging prospect for any motivated young communications professional. Step forward volunteers for the Forces Communication Group.

Richard Bailey was a Senior Press Officer in Whitehall. After an 8 year commission in The Highlanders, culminating in Kosovo, Richard managed the media operation for the Lockerbie Trial in the Netherlands in 2000, worked as press officer at Conservative Central Office during the 2001 General Election, was Head of Media at the Country Land and Business Association, and handled the media operations for the Hutton Inquiry and the Soham Trial.

He is pretty sure he has not been “useless” to the media for some considerable time!

No comments:

Post a Comment